OpenAI's Silicon Valley pivot

What was a research organization is now following dreams of being the next Apple. Plus: Why is everyone suddenly talking about WebGPU again?

Since we have a holiday weekend coming up and I’m still on the other end of a heavy travel week (as well as getting ready for a heavy conference month in June), two columns this week are kind of smashed into one with some additional notes on WebGPU and WebLLM. Enjoy the long weekend!

In January 2007, Silicon Valley luminary Steve Jobs took the stage to explain a device that was “a phone, an iPod, and an internet communicator.” He followed it, to a roaring crowd, by saying, “are you getting it yet?”

Seventeen years later, a handful of employees sat in a room in Silicon Valley speaking with a cheerful synthetic assistant that sounded close enough to Scarlet Johansson’s voice in the film Her that it might as well have been Johansson. And it was lying in the same device: an iPod, a phone, and an internet communicator.

But this time around there’s nothing to “get,” as the most iconic Silicon Valley companies have already made casually pulling products out of science fiction—self-driving cars, buying anything with a press of a button, speaking to friends across the world on demand, and access to nearly the entire corpus of human knowledge—into reality almost a rite of passage.

It seems increasingly obvious OpenAI, and its leader Sam Altman, want to become part of the enduring Silicon Valley lore with a truly Silicon Valley product: a feat of engineering that’s, quite literally, straight out of a movie. And in classic Silicon Valley fashion, there’s simply the expectation of a number of variable sized bumps along the way. Or, as we used to say, “move fast and break things.”

All this, though, is more or less the logical conclusion of the last six months of OpenAI’s operations. Altman, ousted by the board in November last year, engineered a return that presaged a pivot from a research firm into an achieve-the-impossible consumer technology company.

OpenAI has effectively shed its moniker as a research institution in recent weeks not only through its unveiling of that synthetic assistant, but by seemingly moving to an ask-for-forgiveness-not-permission approach to development. Its chief scientist Ilya Sutskever left, and Wired reported that its Superalignment team has disbanded as well. And this week it is dealing with the fallout of that same giggling digital persona sounding way too close to Scarlet Johansson, who declined to participate in developing its “Sky” voice, per a statement from NBC.

OpenAI is now creating one of the kinds of culture-altering company Silicon Valley entrepreneurs dream to achieve—through whatever means are needed to do so. It’s why so many people come to San Francisco in the first place, and with Altman at the helm, OpenAI is becoming a quintessential product-led Silicon Valley company.

Altman has always had very deep ties to Silicon Valley, the San Francisco Bay Area, and San Francisco itself well into the early mobile tech boom. His growing influence in Silicon Valley, before taking over OpenAI, culminated in becoming the president of the industry’s most prestigious accelerator Y Combinator. You can really look no further than the large expat contingent of Stripe—one of Y Combinator’s most successful companies—within OpenAI. Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky’s, another of Y Combinator’s greatest success stories, has emerged as one of Altman’s strongest allies, which you can see in much more detail in an in-depth report in The Information.

Altman quipped that its new voice assistant was straight out of “Her,” a film that received a smorgasbord of Academy Award nominations—including winning the best original screenplay in a year where it was competing with films like American Hustle, Twelve Years a Slave (the Best Picture winner that year), and the much-nearer-future Gravity. Her, in addition to being a great film, offered a glimpse at a future with truly humanlike, empathetic synthetic assistants.

Ever since the film came out, Silicon Valley has desperately tried to make that a reality. But speech technology like Alexa, Cortana, and Siri have long continued to be a dumpster fire and the pathway to that product seemed to just not exist. It was magic in a future that was so far away we couldn’t even see a timeline away from the limited use cases something like Google Assistant could offer.

OpenAI’s unveiling of its latest advanced model, GPT-4o, might as well have been a footnote. Whether or not its voice assistant ends up becoming the ambient companion tech has long dreamed of, OpenAI has also shown that it’s no longer just a research firm creating an API that can power the next-generation of applications.

Instead, OpenAI has pivoted to a company chasing the culture-altering step-change in technology that entrepreneurs have long dreamed about. And it has done so not once, but if you include DALL-E 2, potentially three times—a feat rarely achieved by even the most successful companies in Silicon Valley.

Move fast and break things

Regardless of what’s happened in recent weeks, OpenAI’s voice assistant unveiling was a triumph. The company, hardly a startup any more, needed to create some kind of step-change cultural moment in AI when the vibes were clearly of the “AI is hitting a wall” kind. OpenAI also wasn’t doing itself any favors by running simultaneously one of the most expensive and less performant APIs (on standard benchmarks) for light-to-medium-difficulty problems in GPT-3.5 Turbo.

The “vibe” of its demo was more akin to the release of the iPhone, iPad, or the original release of Google’s we-know-what-you’re-looking-for Instant Search product.

OpenAI, in its last few weeks, effectively looks like a company run by a classic Silicon Valley executive. At the time of his ouster, it represented an interesting potential turning point for the industry that is largely flooded with academics. It’s no surprise that Microsoft, OpenAI’s largest partner, would work as hard as it could to keep an executive like Altman in place.

In April 2009, Y Combinator founder Paul Graham penned an essay about five of the most interesting founders in the last 30 years that at the time included Altman alongside Silicon Valley legends Steve Jobs, Larry Page, and Sergey Brin. Here’s part of what he said in the essay:

What I learned from meeting Sama is that the doctrine of the elect applies to startups. It applies way less than most people think: startup investing does not consist of trying to pick winners the way you might in a horse race. But there are a few people with such force of will that they're going to get whatever they want.

That “force of will” is the north star of entrepreneurship in Silicon Valley. You don’t win on ideas, you win on execution. And the founders listed alongside Altman, and if we wanted to include Mark Zuckerberg as well, routinely skirted with the absolute boundary of what was acceptable at the time—often crossing it just barely before finding a way to avoid the harshest penalties.

In his mission to build an iconic phone, the iPhone 4 brought about the infamous “antennagate” scandal, wherein if you held the phone at the right spots the signal would die out. Apple’s mea culpa here was, well, free iPhone 4 cases for everyone.

While Facebook was routinely the subject of privacy imbroglios, it’s easy to forget that Meta was under a twenty-year consent decree that the FTC hit it with back in 2012. The FTC found in 2019 that it had violated that consent decree and slapped them with a $5 billion fine.

Meta also came under fire for an experiment that intentionally seeded Facebook’s News Feed with content to, essentially, see if it altered the mood of its users.

Google also paid the FTC a fine in 2012 for bypassing Safari’s privacy settings (for a comically low $22.5 million). Google also paid a $170 million fine for violating another privacy law in 2019.

You could walk through the history of the majority of all these iconic tech companies and find these kinds of skirmishes with the norm. That behavior and method of operating distilled down to an early motto at Facebook: move fast and break things. And in AI, one of the strongest “norms” is a heavy focus on safety for a technology with an extreme potential for causing chaos, even if the results are a little mixed.

Altman, born and raised in the classic Silicon Valley mold, is essentially just continuing a long tradition of testing the boundaries as hard as physically possible. You could point to any one of its ongoing engagement with The New York Times over copyright issues, sidelining its Superalignment team, or effectively remaking an iconic sci-fi character without direct involvement with the actress behind her (it?).

It’s not the only voice-cloning scandal we’ve had, though it is certainly the highest profile as it was effectively part of the brand behind its voice assistant (with Altman literally tweeting the reference to Her). The stakes were, and are, high enough and not just limited to Johansson that it made it into the SAG-AFTRA collective bargaining discussions in the industry.

And Y Combinator, practically an institution in Silicon Valley, is built to attract founders and teams that are ready to pull out all stops to build a successful startup. With one of its former leaders at the helm, we could only expect these myriad disputes to be just an early signal of what’s to come as OpenAI looks to remake cultural norms in both tech and beyond.

The fine line between enterprise, consumer, and icon

But despite the release of ChatGPT, which created one of those cultural moments in tech, OpenAI was largely what you’d consider an “enterprise” business not unlike Stripe. It offered a suite of APIs that would potentially power a next generation of technology products, though for the time being that technology is still looking for its killer use case. But most of the experimentation here is, well, enterprise use cases (such as RPA).

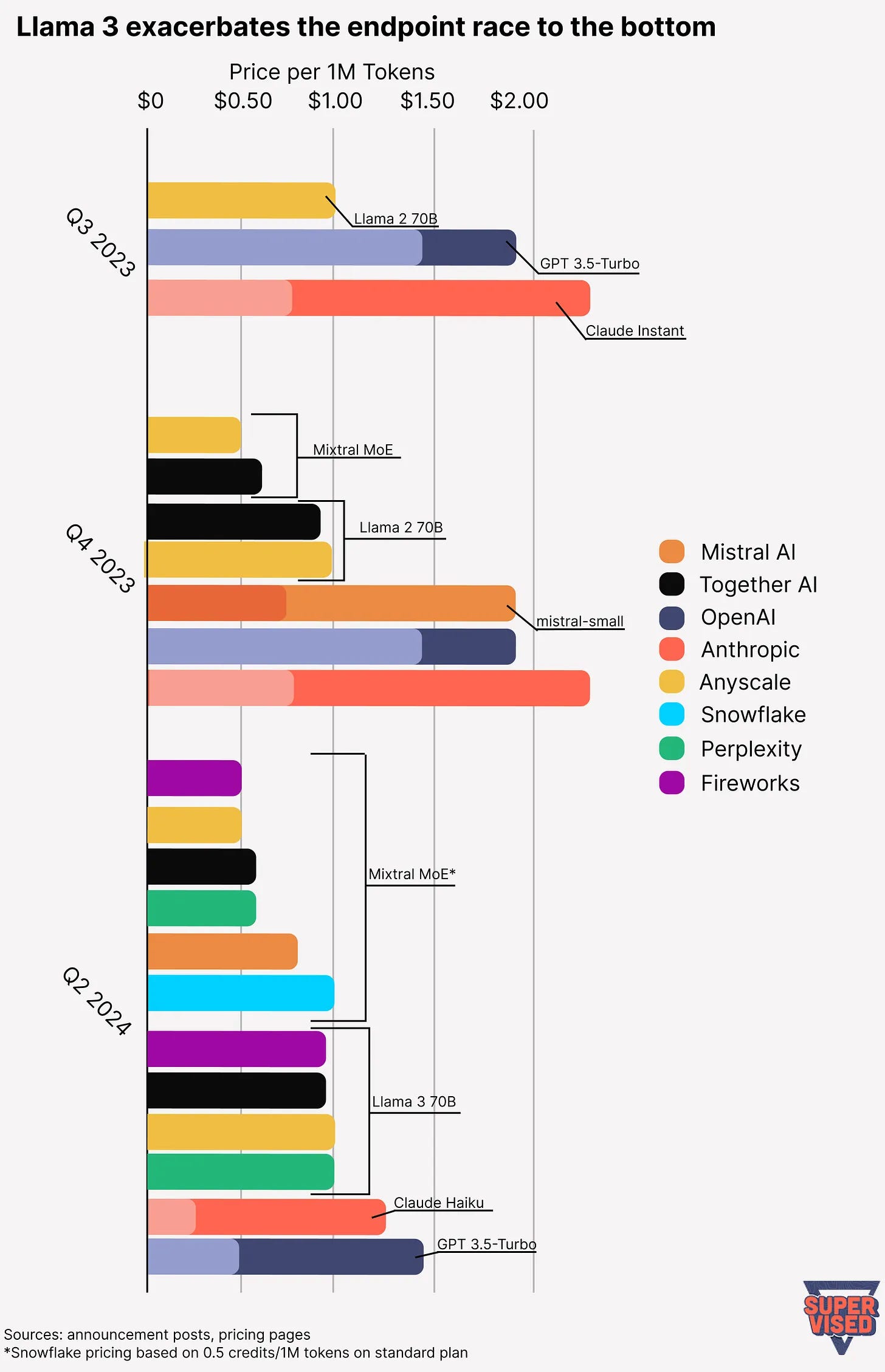

The release of Llama 3, which in many standard benchmarks was highly competitive or more effective than GPT-3.5 Turbo, exposed vulnerabilities to OpenAI’s core enterprise business. A flurry of startups threw up endpoints that could effectively replace GPT-3.5 Turbo with a few lines of code. OpenAI did what it could do—with a price cut to GPT-3.5 Turbo and the release of a batch processing API—but its first-mover and convenience factor advantage was starting to quickly degrade.

Rather than getting a GPT-4 “Lite” model to address that problem, we got a semi-equivalent multi-modal model to GPT-4 that is half the price of GPT-4 Turbo. And while that’s an enormous price cut compared to GPT-4 Turbo (and GPT-4 Classic), it still doesn’t tackle the workhorse model problem OpenAI now faces. Instead, GPT-4o is more in line with competing with Claude Sonnet and Opus, Cohere’s Command-R+ (which developers seem to love), and Mistral’s latest higher-tier mixture-of-experts model and its mistral-large model.

When we step back and look at the pricing in that light—and what OpenAI is trying to do here—it starts to make a little more sense. GPT-4o’s goals are more aligned with what Gemini 1.5 Pro, Mistral’s large model, Claude Opus, and to a certain extent what Command-R+ are trying to achieve: a premium tier. Here’s how the pricing breaks down. (I’m not going to include GPT-4 Turbo, GPT-4 Classic, or Claude Opus, as they basically break the chart and slightly miss the point.)